Honey: A Bee-Loved Sweetener

By Jennie Shurtleff

History of Honey

Up until the late 19th century, refined, crystallized sugar was considered by most people to be a luxury. Although cane sugar might be purchased for special occasions, many people continued to rely on less costly sweeteners that they could gather or produce themselves.

One of the most popular of these alternatives was honey. Honey had been used in Europe for thousands of years. Early cave paintings depict people harvesting it, and residue found in ancient pottery confirms that both honey and beeswax were widely used for food, medicine, and other purposes. Although early efforts at beekeeping likely began much earlier, there is substantial documentation showing that bee domestication was being actively practiced in Europe during the Middle Ages, particularly in monasteries where monks used the beeswax to produce candles. While beeswax candles were a luxury mainly enjoyed by the wealthy or used in churches and monasteries, even commoners during this period used honey to flavor their porridge and other foods.

Given this long-standing reliance on honey as a sweetener, it is not surprising that among the most valued items that European settlers brought to North America in the early 1600s were honey bees. Once released, these bees quickly established themselves in their new environment.

While some American settlers in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries kept apiaries, or groups of managed hives, beekeeping was never an easy endeavor, particularly in northern climes with unpredictable weather. Even seemingly minor events, such as an early spring thaw, could devastate a colony.

And, if a hive survived the winter, there was always the risk of swarming. Swarming frequently happened if a hive became overcrowded. With little warning, some of the bees and a queen would leave the hive while specialized foragers, called scout bees, searched for a site to establish their new colony. If the beekeeper were not quick enough, or if the bees swarmed to an area outside of the beekeeper’s reach, the bees would be lost.

For these reasons, many of our ancestors preferred not to raise bees at all, but instead preferred to harvest honey from the wild that had been produced by feral colonies, often hidden in hollow trees.

Bee-Lining

Bee-lining boxes were often used to track down these feral colonies. Bee-lining boxes were simple, but ingenious. They generally had two compartments that were separated by a sliding door. The first compartment that was accessed by a hinged or sliding door on top of the box would allow the bee tracker to capture bees as they were foraging among flowers for nectar and pollen. Once a bee was captured, the bee tracker would then slide the panel separating the two compartments so that the bee could enter the second compartment where there would be a piece of honey comb filled with sugar syrup. After the captured bees had been given an opportunity to fill up on the sugar syrup, they would be released, one at a time, through the door on top of the second compartment. The bee tracker could then note the direction in which each bee flew as it was released. Since bees tend to fly in a straight line back to their hive, by continuing to release bees -- one at a time -- the bee tracker could narrow down the location of the tree or other structure where the hive was located.

Bee-lining box in the Woodstock History Center’s collection that was donated by Kit Nichols. This bee-lining box has a sliding glass cover, instead of hinged doors on top, to allow the bee hunter to trap and release bees.

Unfortunately, once a feral bee hive was found, early honey hunters often destroyed not only the bees’ home but the colony itself by taking all the honey, thereby depriving the bees of their food supply and leaving them to starve.

Today, skilled apiarists take great care to minimize disturbance when harvesting honey. They remove the surplus stored in the upper chambers of specially-made hives, ensuring that the disturbance to the bees is minimized and that colonies retain enough honey to sustain themselves through the winter.

Bee-Keeping & the Journals of Charles E. Curtis

The Woodstock area has laid claim to a number of skilled beekeepers over the years, including Gaius Cobb, Sy Osmer, and Charles E. Curtis.

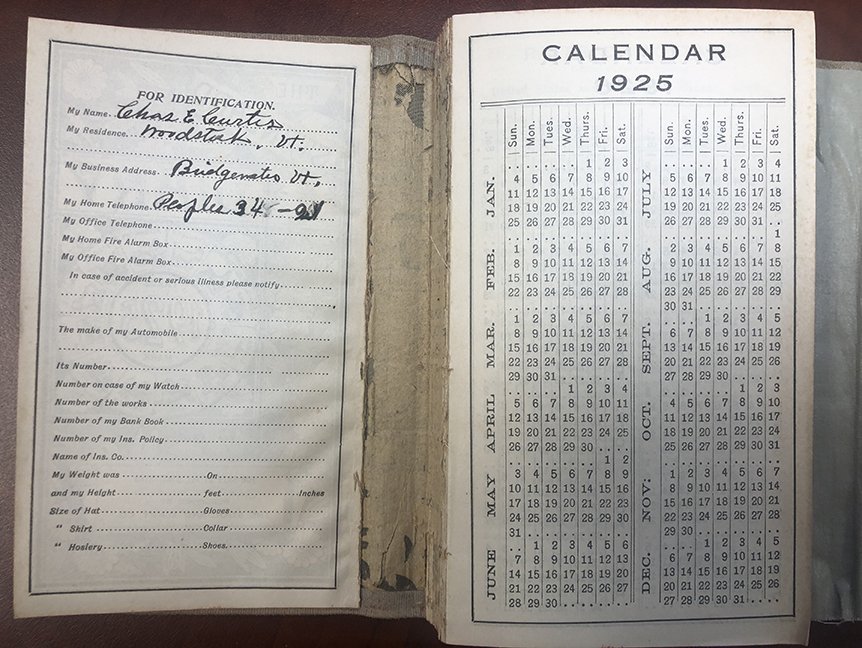

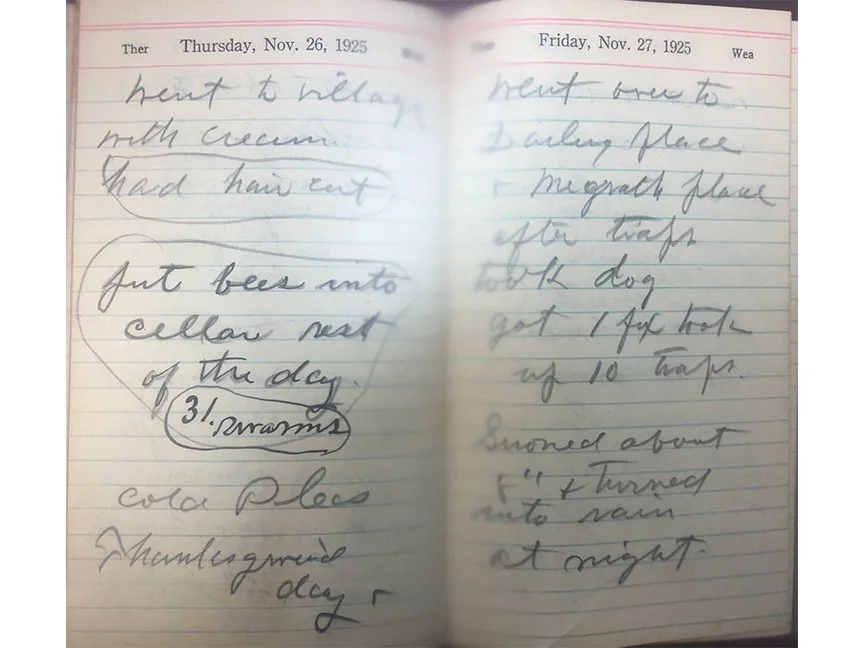

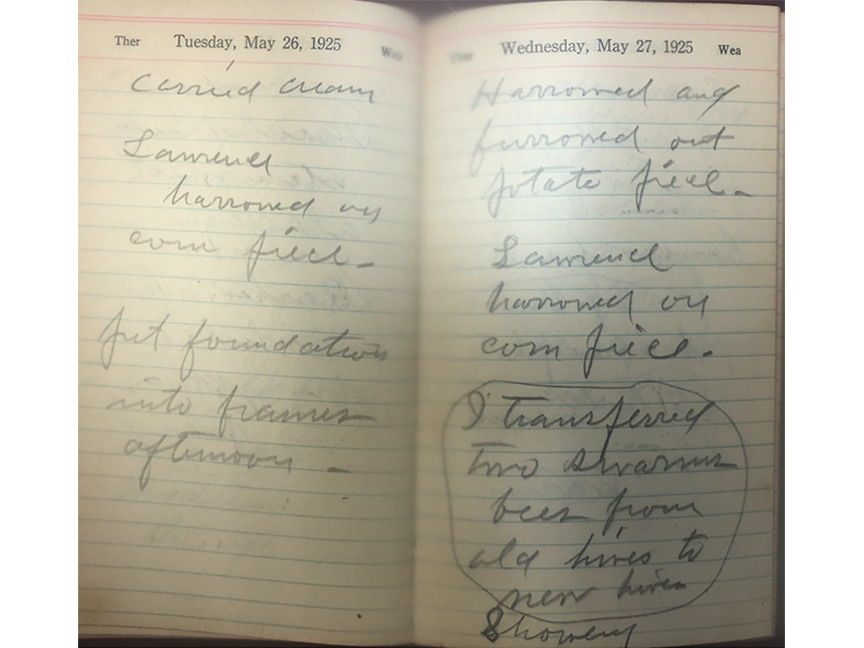

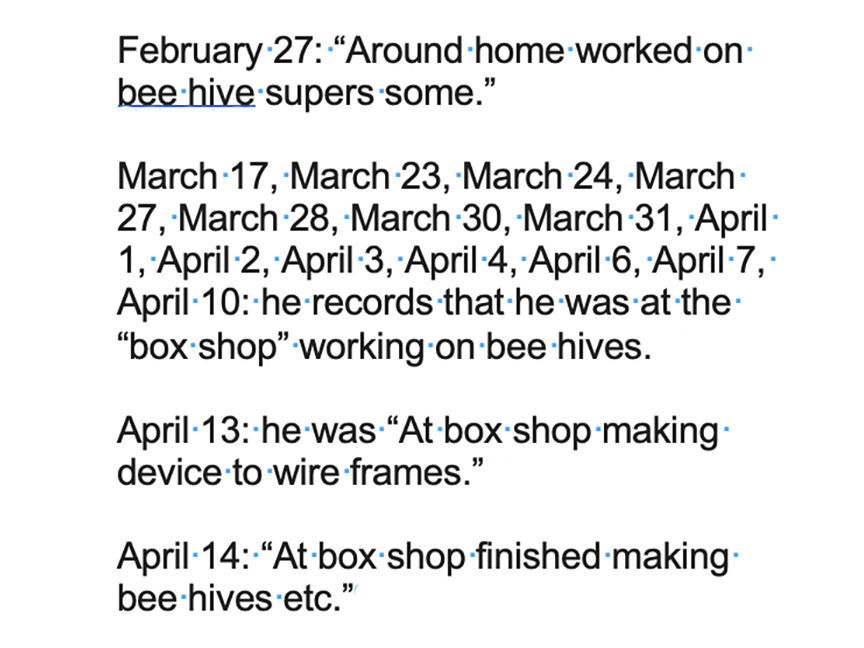

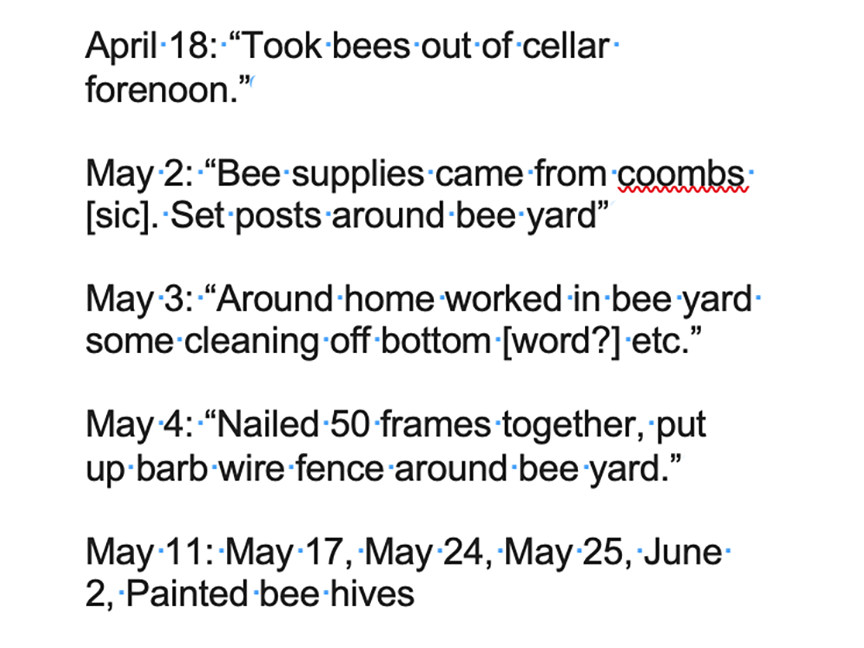

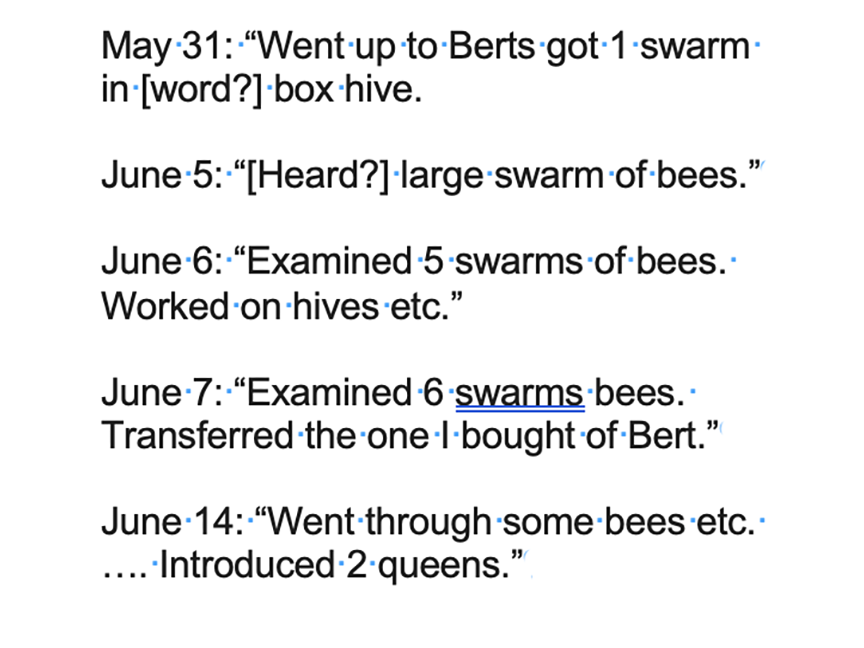

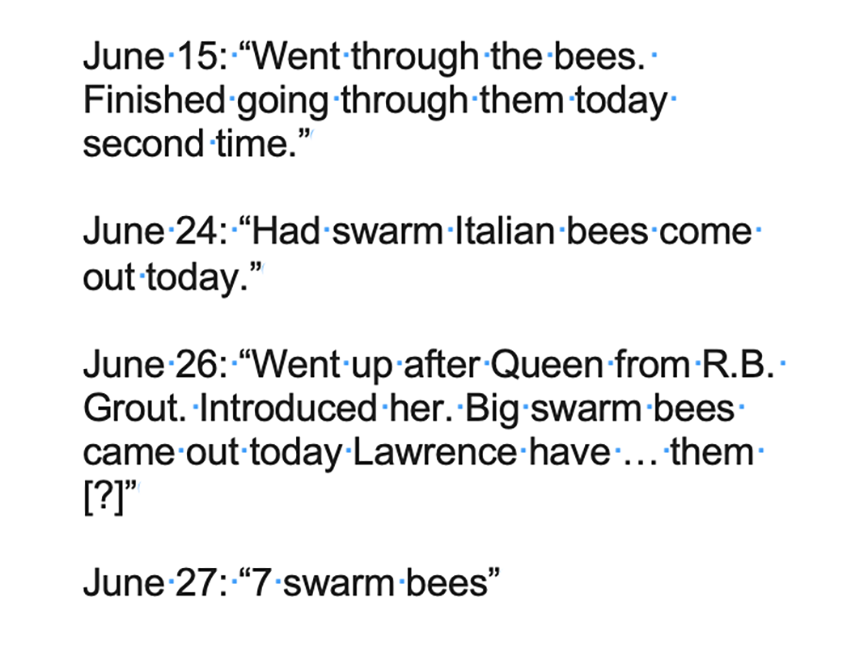

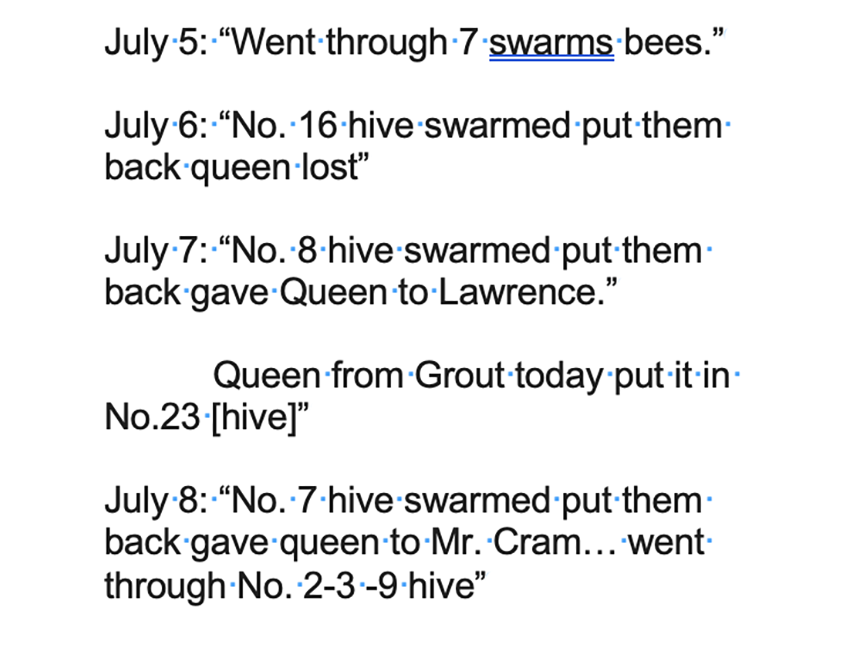

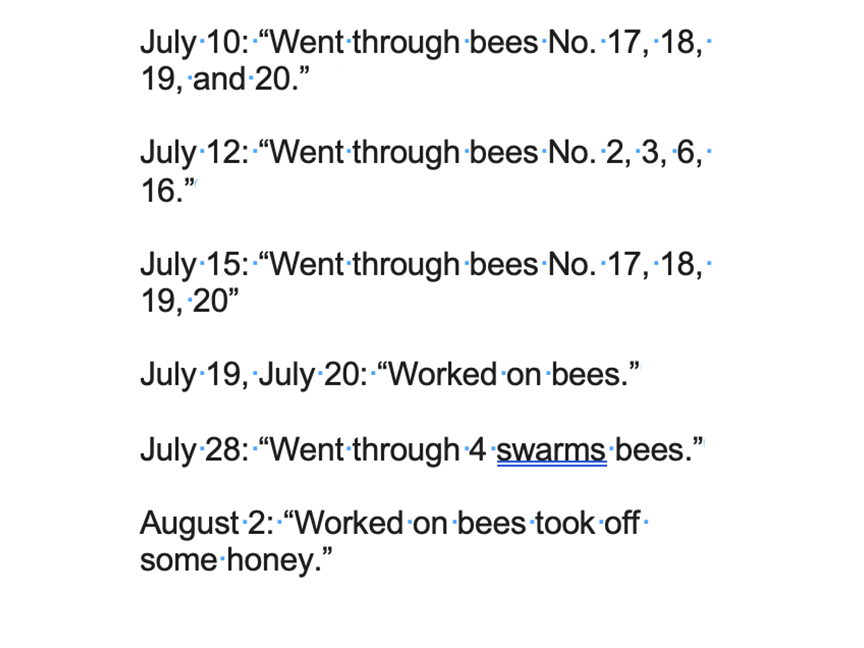

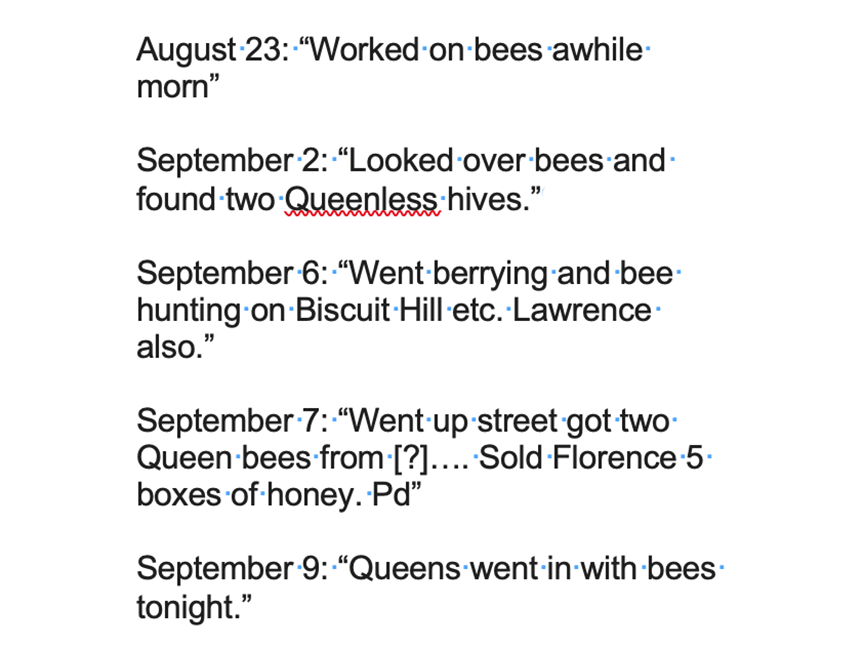

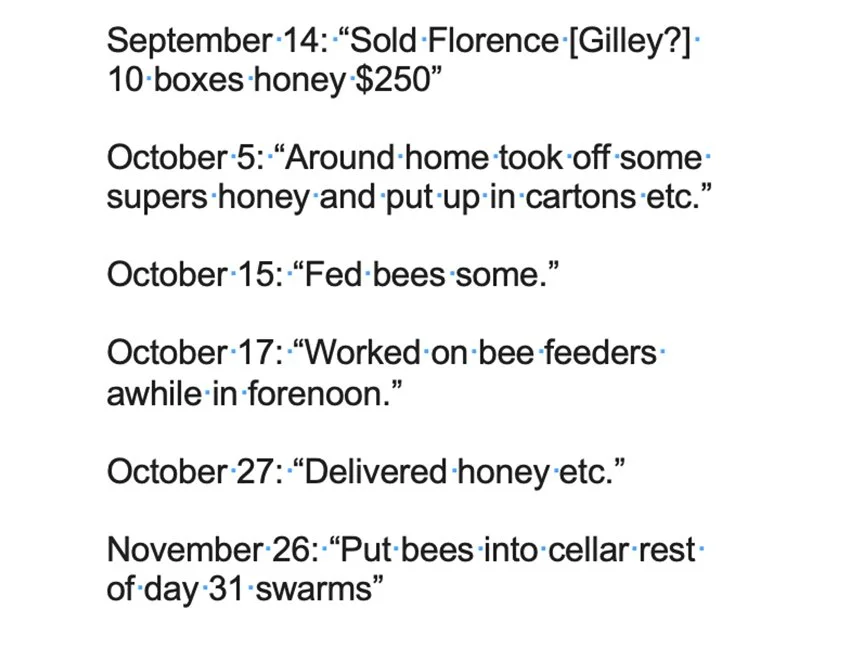

Charles E. Curtis, father of Lawrence Curtis, was a farmer who lived in the section of Woodstock that is near Bridgewater. We know a fair bit about Charles’ beekeeping operation because he kept a journal in the year 1925. This journal, which was donated to the History Center by Dave Green, recorded the many bee-related tasks that Charles undertook in caring for his bees. These activities included constructing and painting bee hives, building a bee yard, bringing the bees out of the cellar in the spring, routinely checking on hives, finding and introducing queens, catching bees that had swarmed, removing and packaging the honey, feeding the bees, and putting the bees in the cellar for winter.

While it is not clear how much money Charles made in the year 1925 from his efforts in keeping bees, by the end of the season, he had 31 “swarms” (hives) of bees, a number of which he appears to have acquired by catching either feral swarms or swarms that had escaped from other beekeepers. That said, he spent countless hours on his bees, including re-patriating his own escapees back into his hives. While the production of honey was likely his main goal at the time, he was also undoubtedly aware of the role bees played as pollinators as this important function of bees had been discovered by Irish botanist Arthur Dobbs over 150 years earlier in the mid 18th century.

Modern research continues to underscore the importance of honey bees as vital pollinators. As bees travel from flower to flower, they transfer pollen, enabling the production of roughly one-third of the world’s food crops. Because of this essential role, honey bees are estimated to contribute nearly $20 billion each year to the United States’ economy.

Of course, honey bees also produce honey itself, which remains a beloved sweetener. Unlike refined white sugar, honey contains trace amounts of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. It is delicious not only as a spread, but also prized as a baking ingredient —just as our forbears often used it long ago.

Historic Recipe Using Honey

Below is one example of a recipe that uses honey as a sweetener from a 1796 cookbook called American Cookery. This recipe for Honey Gingerbread uses honey to reduce the amount of required white sugar.

Measurements and substitutions (such as baking soda for pearlash) have been made in this recipe to make it easier to follow for current-day bakers.

HONEY GINGERBREAD

Ingredients

3 ½ cups flour

1 Tablespoon ginger

1 Tablespoon cinnamon

3 Tablespoon candied orange peel (diced)

1/3 cup white sugar

1 egg

2/3 cup honey

1 ¼ cups sour milk

½ teaspoon pearlash (as a modern-day adaptation, use a ½ teaspoon baking soda).

Combine the flour, ginger, cinnamon, orange peel, and sugar. Dissolve the pearlash (or baking soda) into the sour milk. Mix the egg with the honey, and then combine it with the sour milk mixture. Combine all the ingredients together, and then knead the dough until smooth. Roll the dough to a thickness of a 1/2 inch to 3/4 inch. Then cut the rolled dough into shapes.

Bake at 325°F for 25 minutes.

Note:

The cookbook American Cookery, which originally contained this recipe, was written by Amelia Simmons. It is the first known cookbook that was written by an American. It is also unique in that it emphasized the taste preferences and the types of ingredients that were found in the newly-formed United States.

Unfortunately, there are only four extant copies of the original version of this cookbook, and – alas – they are not in the History Center’s collection. However, some of the recipes from this cookbook, like this one, have been shared online.