Lydia Frances Woodward

By Jennie Shurtleff

Lydia Frances Woodward

When visitors to the Woodstock History Center’s museum walk into the Victorian-style parlor, one of their first questions inevitably is, “Who is the lady in the portrait over the mantel?” The portrait to which they refer is an oversized painting of a young woman, wearing an elegant, low-cut blue gown. In the background is a romanticized landscape that includes pink roses and distant blue mountains.

The subject of the portrait is Lydia Frances Woodward, or “Frances” as she was called by family members. This portrait once hung in the mansion on Mountain Avenue that was originally known as the Woodward Mansion, but in the twentieth century became known as the Faulkner Mansion.

Frances’ Early Life

Frances was born in 1833 in Milbury, Massachusetts. In June of 1847, when she was fourteen years old, she moved with her parents to Woodstock. Precipitating the move was that her father, Solomon Woodward, had purchased the brick mill building (shown in the photo to the left), that is now the Woodstock Recreation Center, on the western edge of the village.

The detail from the Presdee and Edwards map shown above was created in the early 1850s. The areas demarcated in red indicate the property that Frances’ father, Solomon Woodward, acquired in the early days of his tenure as mill owner. His holdings continued to increase as he developed the area with additional double tenements, outbuildings, and a mansion on Mountain Avenue that became the family’s home.

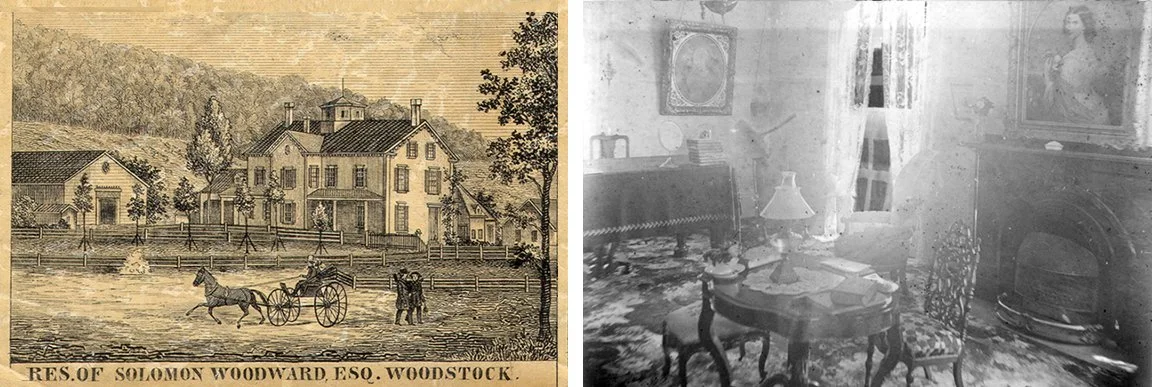

The above image on the left shows the Woodward Mansion on Mountain Avenue. The image on the right shows an interior photo of what appears to be the Woodward’s parlor. Note that the portrait of Frances’ that is now in the Woodstock History Center’s collection once hung in the Woodward mansion above the fireplace mantel.

While the young women who were employed in the woolen mill belonging to Frances’ father worked 14-hour shifts, Frances enjoyed a privileged lifestyle that included attending a private school in Hanover, New Hampshire, serving as the librarian and treasurer for the local Book Club in Woodstock, and studying music in Boston with the noted operatic soprano and vocal pedagogue Hermine Küchenmeister-Rudersdorf, who is often referred to as Mme Rudersdorff.

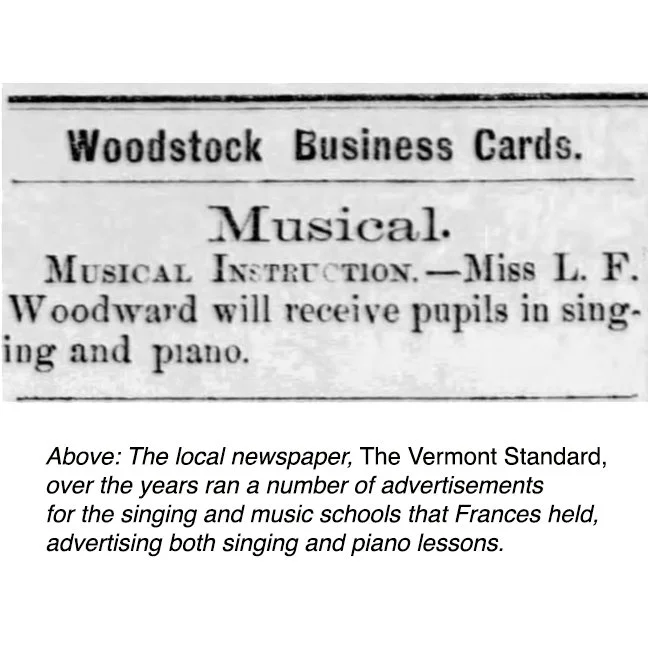

Ultimately, music seems to have been Frances’ most lasting passion. In addition to performing on stage to the adulation of Woodstock audiences, she was also known in the Woodstock area for her efforts in sharing her love of music with others, both by arranging community performances that highlighted local talent and by teaching and mentoring others.

Frances as a Teacher

Frances appears to have enjoyed teaching. One of Frances’ nieces, Lilian H. Marble Ozendam, remembered the interest that Frances took in the musical training of the children in her family. She states in a memoir, “As fast as our numerous family came along Aunt Frances took us in hand (I might add in no uncertain manner!) and endeavored to instruct us in the gentle art of music.”

While only a cursory mention, these sentences suggest that Frances was a woman who enjoyed nurturing the talents of others, but also, she was ostensibly a woman capable of taking charge.

Frances’ Later Life

Such sentiments are echoed in Frances’ obituary, in 1902, in which she was described as “a lady of quite strong personality, of unfailing courage and unflagging perseverance.” In a time when being docile and deferential were often viewed as preferred feminine traits, Miss Frances Woodward’s strong personality appears to have stood out. She was also described as a person who “was not apt to form indiscriminate friendships, but it was especially true of her that she won unusual regard from her intimate friends, and was ever loyal in return.”

This same loyalty also appears to have been extended to at least some family members as her obituary mentions her “self-sacrificing devotion” to her mother (shown in the photo to the left) in her mother’s final years. After her father passed away, just a year or so after her mother, Frances increasingly spent time in Massachusetts where she joined the faculty of Wellesley, a renowned women’s college, and taught voice lessons.

However, she continued to return to Woodstock for the summers, where she stayed at the mansion that she had inherited upon her father’s passing. Ultimately, in 1895, the Woodward mansion was sold, and Frances spent her remaining years in Brookline, Massachusetts.

In the above photo, Frances Woodward is shown on a horse in front of the Woodward Mansion. Presumably the man standing by the horse is her father, Solomon Woodward.

Given her family’s extremely privileged financial situation, Frances Woodward’s story is unusual; however, there are echoes of it in the stories of other young women from the area. One of the many things that stands out about Frances is that she never married. However, in this regard she is not unique as she was but one of a number of young women in Woodstock who remained single. Others included Alice Eaton, Luna Converse, Sarah Hutchinson, and Anna King. All of these women were bright, well-educated, and from well-to-do families. Their reasons for not following the more traditional path of marrying and raising children are unknown. Perhaps as women of means in their own right, they didn’t feel the need to marry for financial security. Or perhaps as women who were well-educated and had developed academic and cultural talents, they wished for a career and were concerned that such aspirations might be abridged by domestic obligations. Or maybe devotion to parents and other family members kept them from pursuing their own families. Or, of course, the reason could be as simple as not meeting the person with whom each wished to spend her life.

Hopefully, more family stories, memoirs, letters, and other information will become available in the future that will help inform us about the lives of individual women during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While shedding light on the lives of specific women, such information — when viewed collectively — may also help us to better understand more universal shifts in the life choices made by women and how these changes impacted longstanding institutions, societal norms, and family relationships.