A Divided Nation: Loyalists in Revolutionary America

By Jennie Shurtleff

Imagine a period in history when our country stood on the edge of revolution, deeply divided and consumed by a crisis of identity. On one side were those who believed the nation's leader should hold broad, centralized power and that they should be loyal to this single ruler. On the other side were those who believed governance should be tempered with a balance of power and ultimately rest with the people. Emotions ran high, and reason often gave way to violence. Citizens harassed one another, and governments threatened dissenters. The period of which I speak, of course, is the Revolutionary War period of American history, from 1775 to 1783.

The Loyalists — often called Tories — believed that colonists in America were British subjects and should remain loyal to the crown. Opposing them were the Patriots, who championed independence and sought freedom from British rule.

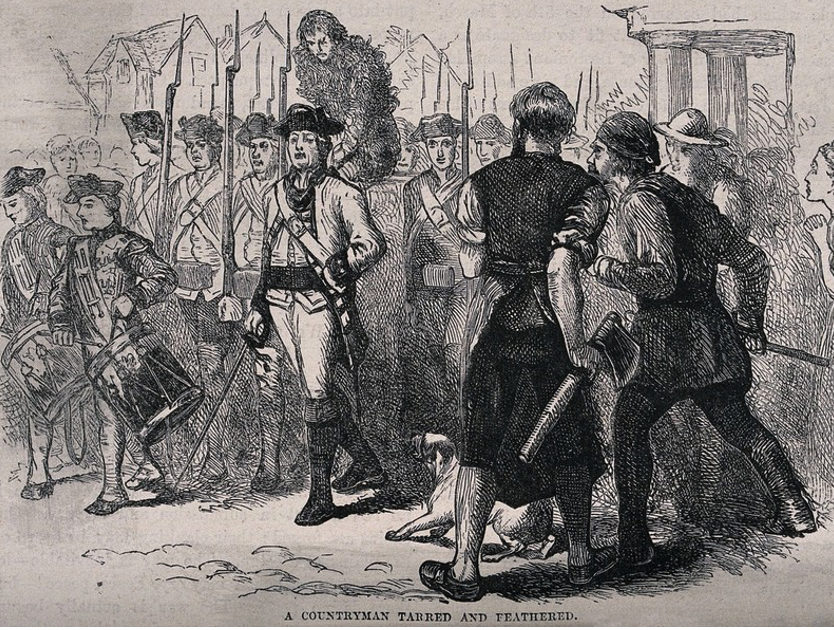

In some cases, the Patriots used harsh tactics to intimidate the Loyalists. One infamous method was tar and feathering. Typically inflicted upon working-class Loyalists, this involved covering the person in hot pine pitch (often used for sealing boats) and then in feathers, leaving them looking like a grotesque bird. The victim would be paraded through town, mocked and humiliated by jeering crowds.

Historic print showing a man who has been “tarred and feathered.” The process involved covering the person in pitch (sometimes over their bare skin), and then coating them with feathers. Although ostensibly the idea was to humiliate the person, the pitch was often very hot and could leave the unfortunate victim’s skin burned and blistered.

Charles Ward Apthorp by John Singleton Copley.

Wealthier Loyalists were often spared physical punishment, but they were not immune to retaliation. Instead, they were often targeted financially. A notable example is Charles Ward Apthorp, a wealthy landowner with ties to Woodstock, Vermont.

Apthorp inherited vast wealth from his father, a successful Boston merchant who profited from trade — including the slave trade. By the eve of the Revolution, Charles owned land in Massachusetts, Maine, and Vermont.

One 1772 lotting map identifies him as a major landholder in Woodstock. Though he lived in New York — in what is now the Upper West Side of Manhattan — his real estate investments spanned New England. His grand mansion was located between what are now 90th and 91st Streets and Columbus Avenue. It featured luxurious elements like a mahogany-paneled dining room, marble floors, and a sweeping staircase.

A staunch Loyalist, Apthorp's position became precarious once the war broke out. His house, due to its prominence, was used at various times as headquarters by both Patriot leader General George Washington and British General William Howe. While the British occupied New York, Apthorp served the Crown in multiple roles, including as manager of the Court of Police.

Drawing of the Apthorp mansion in New York. This mansion was torn down, but used to stand on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

After the British defeat, Apthorp was arrested as an enemy of the United States. Although he was allowed to keep his New York home, his properties in Massachusetts, Maine, and Vermont were confiscated and sold.

In Woodstock, his land holdings included valuable tracts on the town’s western edge near the Bridgewater line and in South Woodstock near the Reading line. One of these properties was sold to Jonathan Farnsworth. The deed explicitly states that it had previously belonged to Charles Apthorp of New York, “an enemy of the United States of America.”

Historian Henry Swan Dana recounts Apthorp’s efforts to reclaim his land after the war. In 1794, a legal battle in Windsor County resulted in a verdict against him. His legal team argued the trial was flawed — citing irregularities such as the jury separating before sealing the verdict and the court's refusal to admit exculpatory evidence. Despite these efforts, the court denied a new trial, and Apthorp permanently lost his 7,000 acres in Woodstock.

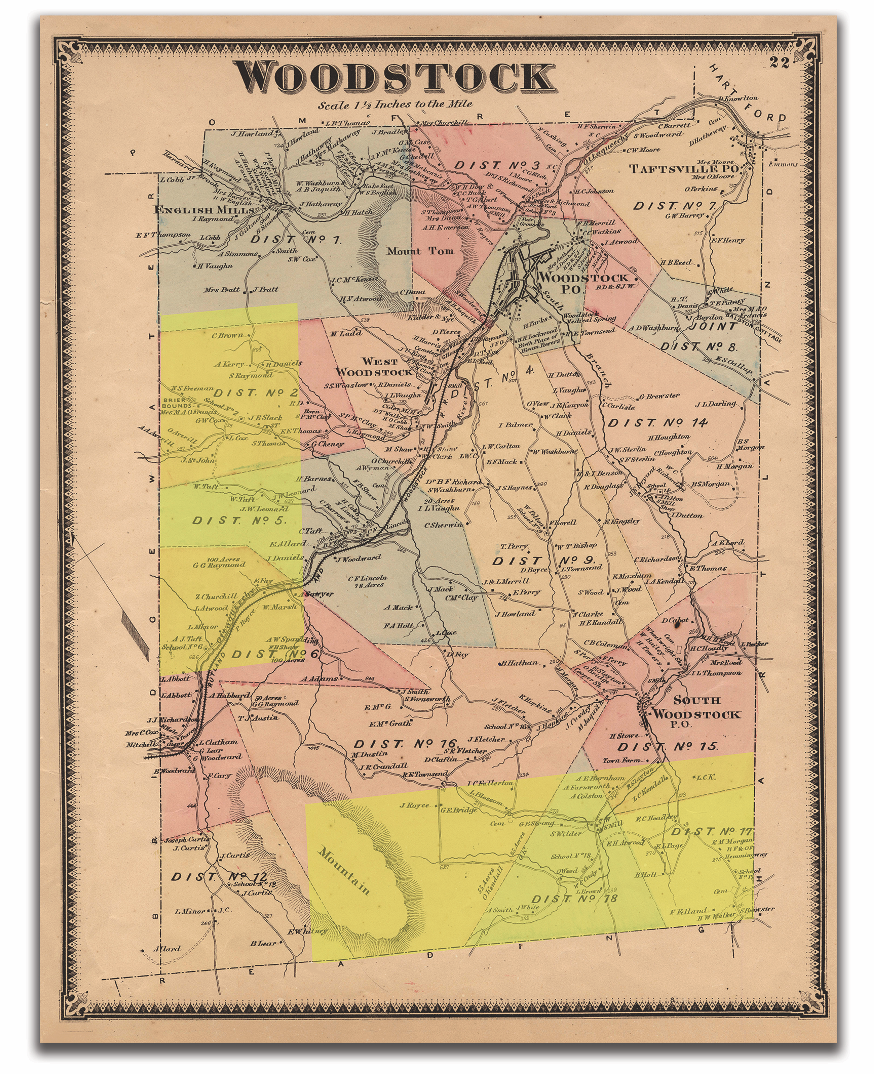

Woodstock “Beers” map with highlights.

The areas highlighted in yellow on this map show the two large tracts of land, totalling about 7,000 acres, that were owned by Charles Ward Apthorp before the Revolutionary War.

Apthorp was not alone. Others with Loyalist sympathies also faced persecution — including Dr. Josiah Sturtevant, father of Deborah Sturtevant, who later married Dr. Standish Day of Woodstock.

At the outbreak of the Revolution, Patriots planned to tar and feather Dr. Sturtevant of Halifax, Massachusetts. Forewarned by friends, he prepared that day by loading up his saddlebags with medicines and then secreting his horse in the nearby woods so that he could flee at night under the cover of darkness. However, soon after retrieving his horse that evening and starting his journey toward Boston, he was spotted by a neighbor and shot at, losing his saddlebags in the chaos. He reached Boston safely but died three weeks later.

His widow, Lois Sturtevant, wrote heartbreakingly in her journal:

“August 18, 1775. My dear husband departed this life in the 55th year of his age at Boston, where he was drove by a mad and deluded mob for no other reason than his loyalty to his Sovereign. God forgive them and grant that his death may be sanctified to me and the children for our Souls everlasting good.”

A neighbor who found the lost saddlebags returned them to Lois — but only after demanding a dollar in payment. Years later, that same man moved to Woodstock. By chance, he crossed paths with Dr. Standish Day, now married to Deborah Sturtevant. Unaware of the connection, the man proudly recounted the story of charging a dollar to a Loyalist’s widow. Dr. Day, hearing the tale, quietly added the dollar as a charge on the man’s bill — a small, symbolic act of justice.

What makes this story especially poignant is that Dr. Day had fought as a Patriot. Yet he chose to marry the daughter of a Loyalist and, in his quiet way, acknowledged the shared suffering of a fractured nation and a family. Their union is symbolic of a larger truth: despite the violence and bitterness of revolution, Americans eventually came together — forging a new identity, a new nation, and a commitment to principles greater than division.