Independence Day in Woodstock

By Jennie Shurtleff

In the nineteenth century, one of the most anticipated holidays of the year was Independence Day. In fact, in 1899 the editors of the local newspaper Spirit of the Age refer to the holiday as “Woodstock’s Greatest Day.”

So how was this special day celebrated?

Charles Morris Cobb was a teenage boy living in West Woodstock. He describes that in 1848 the preparations for the holiday began about three days in advance as the “boys of the flat” (West Woodstock), met on the mill logs, presumably located at Daniels’ Mill, and decided to purchase $1.35 of gun powder so that they could celebrate Independence Day “appropriately.” “Appropriately” to a bunch of teenage boys meant with cannons and a great deal of noise.

On the evening of July 3, Charles went to help two other West Woodstockers, George Bennett and Ed Woodward, clean and ready the cannons that they were planning to fire. The three worked until about 10:00 pm, and then went to bed, figuring that they would catch 2 hours sleep.

They must have been tired because they overslept and were awaken at 12:30 am by the sound of a cannon going off. That signaled the start to a cannon fest in which the boys fired their cannons, without cessation, until 9:00 am. At which time they took a break from firing and ate breakfast.

One might think after 8 and a half hours of firing cannons that the boys would be ready to quit. But, no! After replenishing their supplies of gun powder at the Green (a term used to refer to the Village of Woodstock at this time), the boys took a two-hour nap from noon to 2 pm, and then once again readied their cannons for another two-hour round of cannon fire. By 4:00 pm, they left and went home. Charles notes that he was quite tired and went to bed early that night. He also states that: “There was a continual ringing in my ears for 6 months after and for the next 3 days I couldn't hear hardly anything, if one wished to make me understand they must holler 3 times at least. We had some company when I arrived [home after firing cannons all day], and I played [the fiddle] a little, but father said I made it squeak so, and played so loud & harsh, that I spoil'd it all, but I didn't know it, on the contrary. I rosined the bow again, and bore on with all my might wondering all the time what had got into the fiddle, to prevent its making any noise.”

Nearly fifty years later, on July 11, 1896, the Spirit of the Age, states with regard to the Fourth of July holiday jubilations:

“Woodstock did not celebrate the Fourth, and after the early morning salute of guns and bells the day was comparatively quiet. The racket began promptly at midnight, a bonfire blazing on South street, near the Inn, bells ringing for nearly an hour, and the artillery on Mt. Peg booming till daybreak, the latter being as usual under the command of Col. Lute Raymond.”

The following year, on June 19, 1897, the Spirit of the Age states: “There has been no talk of a fourth of July celebration and the boisterous duty of awakening dormant patriotism will probably again fall to Col. Lute Raymond, the veteran cannoneer, who for a quarter of a century or more has once a year dragged his forty-pounder up on Mount Peg and boomed away the night through, to the distraction and exasperation of sleepless villagers.”

In 1899, A Spirit of the Age article mentions that the holiday festivities that year began with “the gun salute in the morning. This, by the way, kept up for nearly 24 hours, and with the accompaniment of tin horns, torpedoes and cannon crackers, was enough to shatter the nerves of even those not ordinarily disturbed by this annual racket… Lute Raymond handled the cannon, as he has for 30 or 40 years, and if he ever missed a year he made up lost time Tuesday by overworking his artillery.”

Lute Raymond, pictured above, was known as the “Keeper of the Cannon.” He safe guarded the cannon from “enemies” who tried to steal and silence it. Lute’s zeal (and that of the “boys from the flat”) for the celebrating the holiday with artillery appears not to have been universally shared.

© Woodstock History Center

That year, in addition to the various groups with cannons firing off their artillery, at the Fair Ground (present-day Billings Farm) there were horse and bicycle races.

The following year, on June 30, 1900, the Spirit of the Age announced “Plans for Woodstock’s Celebration Now Well Under Way.” This article notes that “A bicycle parade, sports, music, and fireworks will be the features of Woodstock’s celebration of the 4th of July, and the various committees are now busily engaged in promoting the success of the holiday events.”

For the bicycle parade, participants were encouraged to decorate their bicycles. The promise of “liberal prizes” was dangled to entice participants to decorate and join the parade. The “athletic sports” contests were being held on the south side of the park, and included such things as pole vaulting and running, and a greased pig was turned loose on Vail Field. [For those unfamiliar with a greased pig, a young pig (smeared with grease) was released and darted about, in a state of fear and confusion, while participants ran after it to catch it. Whoever was able to catch the pig got to keep it.]

In the year 1900, there was also a baseball game that was going to be held on Vail Field featuring the rival teams of Woodstock and Bridgewater. The day of festivities was set to close with a display of fireworks on Vail Field.

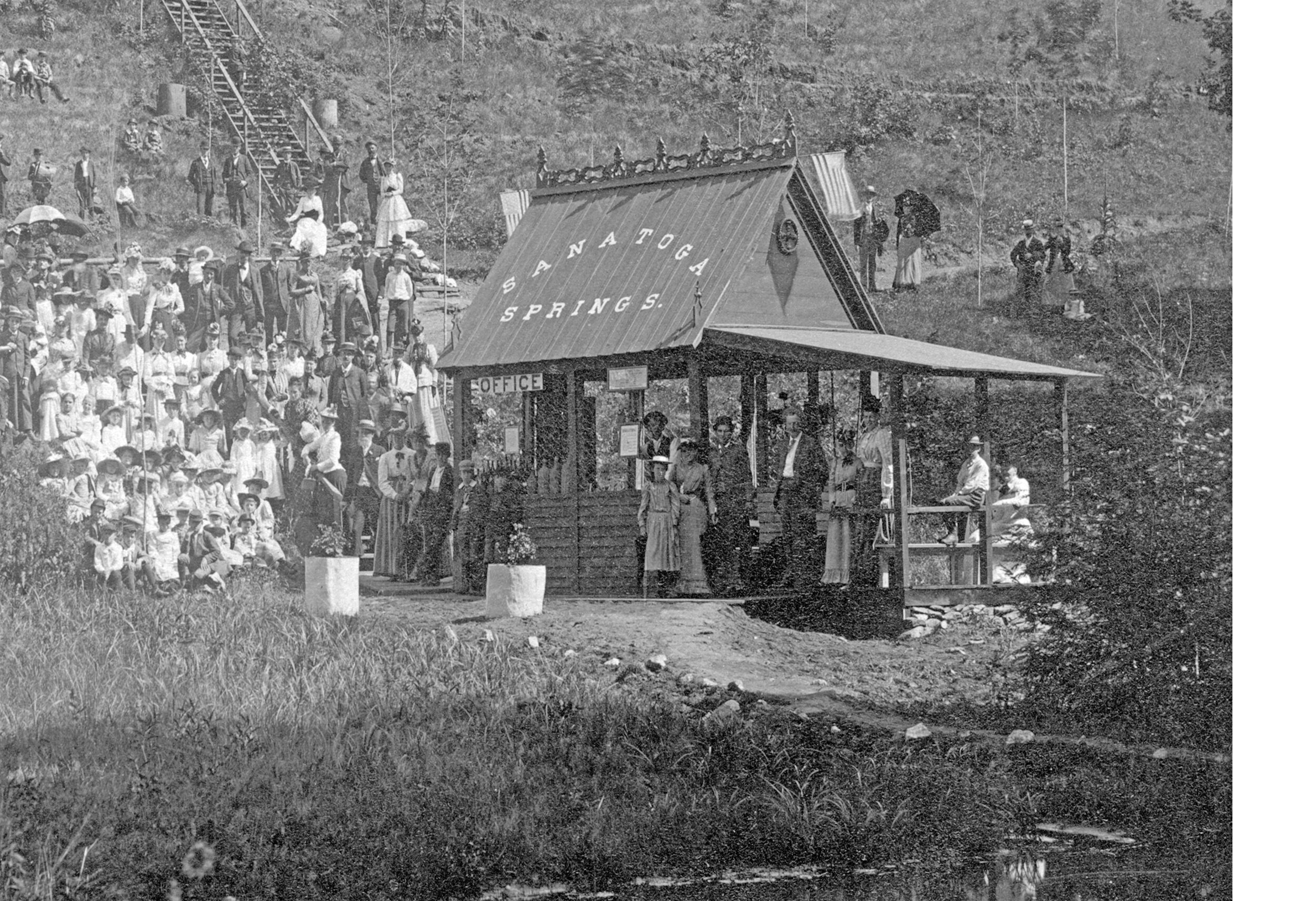

While many of the Fourth of July festivities were held in the center of the village, in the 1892 a large celebration was held at Dearborn Park (also known as Sanatoga Springs) on Dunham Hill. Approximately 500 guests attended. A boy was stationed by the spring house, ready to dip people’s glasses in the water. The article notes that “A careful analysis made by a competent New York chemist shows the water to have strong medicinal properties, holding in solution sulphur, magnesia, iron, and other mineral substances.”

Following a dinner, there was a series of games and races that included a one-hundred yard dash foot race, a bicycle race, an “old men’s race” (eligible contestants had to be 40 years old), an obstacle race, and the throwing of dumbbells. All the games and races appeared to have only male contestants. It is not clear whether the females present chose not to participate, were not allowed to participate, or whether the writer of the article simply chose to report only the men’s events.

Dearborn Park, also referred to as Sanatoga Springs, was located halfway between Woodstock Village and South Woodstock.

The above photo shows a gathering at the park, although the photo is undated so we do not know if the photo was taken at the time of the July 4, 18__ , celebration.

© Woodstock History Center

One of the larger 19th-century Independence Day celebrations predictably occurred in 1876, with the United States of America’s Centennial birthday. Thirteen-year-old Edward “Ned” Dana, who lived in Woodstock on Elm Street (present-day site of the Woodstock History Center), wrote about the events in his diary. Since on July 4th, it rained all day, the fireworks were postponed until Friday, July 7th when they were set off at the “head of the Park” and there was dancing afterwards. On the 4th of July, despite the rain, “The Horribles” came out at 9:30. “The Horribles” refer to a parade of men wearing grotesque or comic costumes. It was a traditional 4th of July activity in many 19th-century communities. The tradition appears to have started on July 4, 1851, when a parade was held to parody the “Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts.” Some towns, followed suit as a way of satirizing public figures and politicians, and began holding their own “Ancient and Horrible” parades.

Photo of Horribles Parade in Woodstock. Date unknown. Notice the man dressed as a woman next to the oxen, while a group of little girls look on. © Woodstock History Center.

The newspaper Spirit of the Age provides a more detailed account than Ned Dana of the Centennial Fourth of July Celebration, some of which is quite candid. The newspaper’s editors write:

“We predicted that there would be a million of people here, on that day, but it fell short a little, and good judges set the number at from 5000 to 8000. The Horribles opened the day’s performance by parading the principle streets, and they were the most horrid horribles any mortal ever saw, and it must have taken genius, time and money to get up such a company. Next came the ‘Floodwoods’ under the command of Capt. L W Wilson, headed by martial music… C P Marsh, Esq., was the orator of the day, Chauncey Richardson, Esq., the local historian… and A E Simmons, Esq., toastmaster. All performed their parts well, although we thought friend Marsh quite tedious on dead and buried political issues. Nevertheless it was scholarly. The committee of arrangements worked like beavers, but they were not supported by sub-committees as no such ‘heap folks’ was expected, and they did not organize thoroughly enough for the occasion, but relied too much on their own efforts, which was too much for them. Give them another chance and see if they wouldn’t do different in some respects. No person ever did do a piece of work the first time to suit him. The committee did well—did all they could. There was freedom; there was plenty to eat and drink. There was no side show to humbug anybody, and had it not been for the rain it would have been the best celebration that was ever held in Vermont. The rain spoiled most much of the free lunch, and shoats of boys spoiled more of it, for the want of somebody to knock them on the nose with a club and made them stand back. The rain spoiled most of the Chinese lanterns, and the open air dance and fire-works had to be postponed until Friday evening, when over 3000 people assembled to finish up the fourth of July on the 7th… It was thoroughly Democratic, and all, without regard to wealth or position, ‘waded in.’… It was a proud day for Woodstock and will pass into history as such.”

One of the local competing papers, The Vermont Standard, provides additional details on the day including that the parade of Horribles was a company of approximately 60 young men “dressed in all conceivable costumes, some on the poorest horses to be found, some in carts and rickety wagons, some on foot, and all thoroughly masked, paraded the streets at half past nine o-clock and were the occasion of a great deal of sport.” The newspaper goes on to state “All known (and some unknown) types and nationalities” were depicted in this parade. One can assume, given the spirit of the parade, that many of these “types and nationalities” were shown in less than flattering ways, as were women and national symbols. The part of the “British lion” was played by “a hog snoozing in a crockery crate,” the “representatives of woman’s rights” were depicted as a man at the wash tub while his wife was composedly driving, and “the girl of the period” was “dressed in stunning style, with the pullback disease so severely fastened upon her as to make it almost impossible for her to keep up with the company.” Being unfamiliar with the term “pullback disease,” I looked it up on the internet. It must be a made-up, colloquial term as it didn’t come up in the search. However, the fact that it is termed a “disease” conveys the sense of an uncharitable portrayal. Fortunately, by the turn of the century, the tradition of the parade of Horribles had fallen out of vogue in Vermont while other traditions, such as picnics and sporting events, have persisted.